Doris Lessing Quiz Questions

1. When did Doris Lessing win Nobel Prize for Literature?

a) 2007

b) 1999

c) 2004

d) 1996

2. What was Doris Lessing’s original name?

a) Emily Maude McVeagh

b) Doris May Tayler

c) Jane Somers

d) Martha Quest

3. When was Doris Lessing born?

a) 10 February 1929

b) 28 June 1914

c) 15 August 1918

d) 22 October 1919

4. Where was Doris Lessing born?

a) Plymouth

b) Salisbury

c) Kermanshah

d) Durban

5. Where did Doris Lessing live in 1925-1949?

a) Southern Rhodesia

b) Northern Rhodesia

c) Nyasaland

d) Bechuanaland

6. Which school did Doris Lessing attend?

a) St. George’s School

b) Dominican Convent High School

c) St. Columba’s Middle School

d) St. David’s School

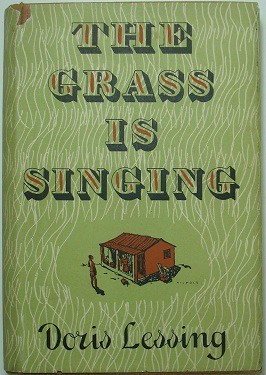

7. Which was Doris Lessing’s first novel?

a) A Ripple from the Storm

b) The Sweetest Dream

c) The Summer Before the Dark

d) The Grass Is Singing

8. When did Doris Lessing write The Golden Notebook?

a) 2000

b) 1974

c) 1962

d) 1988

9. When did Doris Lessing die?

a) 15 March 2004

b) 7 April 1995

c) 26 September 1997

d) 17 November 2013

10. Where did Doris Lessing die?

a) Teheran

b) London

c) Pretoria

d) Washington

Doris Lessing Quiz Questions with Answers

1. When did Doris Lessing win Nobel Prize for Literature?

a) 2007

2. What was Doris Lessing’s original name?

b) Doris May Tayler

3. When was Doris Lessing born?

d) 22 October 1919

4. Where was Doris Lessing born?

c) Kermanshah

5. Where did Doris Lessing live in 1925-1949?

a) Southern Rhodesia

6. Which school did Doris Lessing attend?

b) Dominican Convent High School

7. Which was Doris Lessing’s first novel?

d) The Grass Is Singing

8. When did Doris Lessing write The Golden Notebook?

c) 1962

9. When did Doris Lessing die?

d) 17 November 2013

10. Where did Doris Lessing die?

b) London

Originally posted 2017-01-19 00:34:50.

Pls Can U Show Me The First Page Of This Novel; The Grass Is Singing.

Pls I Need A First Page Of Doris Lessing( THE GRASS IS SINGING)

MURDER MYSTERY

By Special Correspondent

Mary Turner, wife of Richard Turner, a farmer at Ngesi, was found murdered on the front verandah of their homestead yesterday morning. The houseboy, who has been arrested, has confessed to the crime. No motive has been discovered.

It is thought he was in search of valuables.

The newspaper did not say much People all over the country must have glanced at the paragraph with its sensational heading and felt a little spurt of anger mingled with what was almost satisfaction, as if some belief had been confirmed, as if something had happened which could only have been expected. When natives steal, murder or rape, that is the feeling white people have.

And then they turned the page to something else.

But the people in `the district’ who knew the Turners, either by sight, or from gossiping about them for so many years, did not turn the page so quickly. Many must have snipped out the paragraph, put it among old letters, or between the pages of a book, keeping it perhaps as an omen or a warning, glancing at the yellowing piece of paper with closed, secretive faces. For they did not discuss the murder; that was the most extraordinary thing about it. It was as if they had a sixth sense which told them everything there was to be known, although the three people in a position to explain the facts said nothing. The murder was simply not discussed. `A bad business,’ someone would remark; and the faces of the people round about would put on that reserved and guarded look. `A very bad business,’ came the reply – and that was the end of it. There was, it seemed, a tacit agreement that the Turner case should not be given undue publicity by gossip. Yet it was a farming district, where those isolated white families met only very occasionally, hungry for contact with their own kind, to talk and discuss and pull to pieces, all speaking at once, making the most of an hour or so’s companionship before returning to their farms where they saw only their own faces and the faces of their black servants for weeks on end.

Normally that murder would have been discussed for months; people would have been positively grateful for something to talk about.

To an outsider it would seem perhaps as if the energetic Charlie Slatter had travelled from farm to farm over the district telling people to keep quiet; but that was something that would never have occurred to him. The steps he took (and he made not one mistake) were taken apparently instinctively and without conscious planning. The most interesting thing about the whole affair was this silent, unconscious agreement. Everyone behaved like a flock of birds who communicate – or so it seems – by means of a kind of telepathy.

Long before the murder marked them out, people spoke of the Turners in the hard, careless voices reserved for misfits, outlaws and the self-exiled. The Turners were disliked, though few of their neighbours had ever met them, or even seen them in the distance. Yet what was there to dislike? They simply `kept themselves to themselves’; that was all. They were never seen at district dances, or fetes, or gymkhanas. They must have had something to be ashamed of; that was the feeling. It was not right to seclude themselves like that; it was a slap in the face of everyone else; what had they got to be so stuck-up about? What, indeed! Living the way they did! That little box of a house – it was forgivable as a temporary dwelling, but not to live in permanently. Why, some natives (though not many, thank heavens) had houses as good; and it would give them a bad impression to see white people living in such a way.